When you’re older, your body doesn’t process medicine the same way it did when you were 30. A pill that once worked perfectly might now make you dizzy, confused, or even sick. That’s not because the drug is broken-it’s because your body has changed. Aging affects how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and cleared from your system. Ignoring these changes puts seniors at serious risk. In fact, medication dosage adjustments for aging bodies and organs aren’t optional-they’re essential to avoid hospital visits, falls, and even death.

Why Your Body Changes How It Handles Medicine

As you age, your organs don’t just slow down-they rewire how they work. Your stomach produces less acid, which means some pills don’t dissolve as well. Your liver, which breaks down most drugs, loses about 30-50% of its processing power after age 65. Your kidneys, responsible for flushing out medications, lose roughly 8 mL of filtering capacity per decade after age 30. By 70, nearly half of all adults have kidney function low enough to require dose changes. Even your body composition shifts. You lose muscle and gain fat. That means water-soluble drugs like digoxin or lithium build up in your system because there’s less fluid to dilute them. Fat-soluble drugs like diazepam stick around longer because they’re stored in extra fat tissue. The result? A drug meant to last 12 hours might linger for 24 or more. That’s why a standard dose can become toxic.The ‘Start Low, Go Slow’ Rule

The gold standard in geriatric prescribing isn’t complicated: start with less, wait longer, and adjust carefully. This isn’t just advice-it’s backed by decades of research from the American Geriatrics Society and the FDA. For example, gabapentin, often used for nerve pain, is typically started at 300 mg daily in younger adults. In seniors, doctors begin at 100-150 mg. Metformin, a common diabetes drug, can’t be used at all if kidney function drops below 30 mL/min. Even then, the dose is cut in half. This approach isn’t about being overly cautious. It’s about precision. A 75-year-old with normal blood pressure might need only half the dose of a blood pressure pill that works fine for a 50-year-old. Too much? They could pass out, fall, and break a hip. Too little? Their blood pressure stays high, increasing stroke risk. The goal isn’t to treat numbers on a chart-it’s to keep the person safe and functional.How Doctors Calculate the Right Dose

There’s no one-size-fits-all formula, but two methods are widely used. The first is the Cockcroft-Gault equation, which estimates kidney function using age, weight, and a simple blood test for creatinine. For women, you multiply the result by 0.85. If the calculated creatinine clearance falls below 50 mL/min, most kidney-cleared drugs need a dose reduction. For drugs processed by the liver, doctors use the Child-Pugh score. It looks at things like bilirubin levels, albumin, and fluid buildup. A score of 7-9 means moderate liver trouble-dose should be cut by half. A score of 10-15? The drug might need to be stopped entirely. Some drugs, like warfarin or digoxin, have narrow safety windows. Digoxin’s target level in seniors is 0.5-0.9 ng/mL. In younger people, it’s 0.8-2.0. Too high? Irregular heartbeat. Too low? No protection against heart failure. That’s why therapeutic drug monitoring matters-but here’s the catch: it’s only available for about 15% of commonly prescribed medications.

The Most Dangerous Drugs for Seniors

The 2023 Beers Criteria® from the American Geriatrics Society lists 30 classes of drugs that should be avoided or used with extreme caution in older adults. These aren’t obscure medications-they’re everyday prescriptions.- Benzodiazepines (like lorazepam or diazepam): Increase fall risk by 50%. They don’t just make you sleepy-they mess with balance and reaction time.

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen): Raise the risk of stomach bleeding by 300%. A simple pain reliever can cause internal bleeding in someone with thinning stomach lining.

- Anticholinergics (found in many sleep aids, bladder meds, and even some cold pills): Double the risk of dementia with long-term use. Even over-the-counter diphenhydramine (Benadryl) belongs here.

- Antipsychotics (used off-label for dementia behavior): Increase stroke risk by 30% and death risk by 1.6 times.

Polypharmacy: The Silent Killer

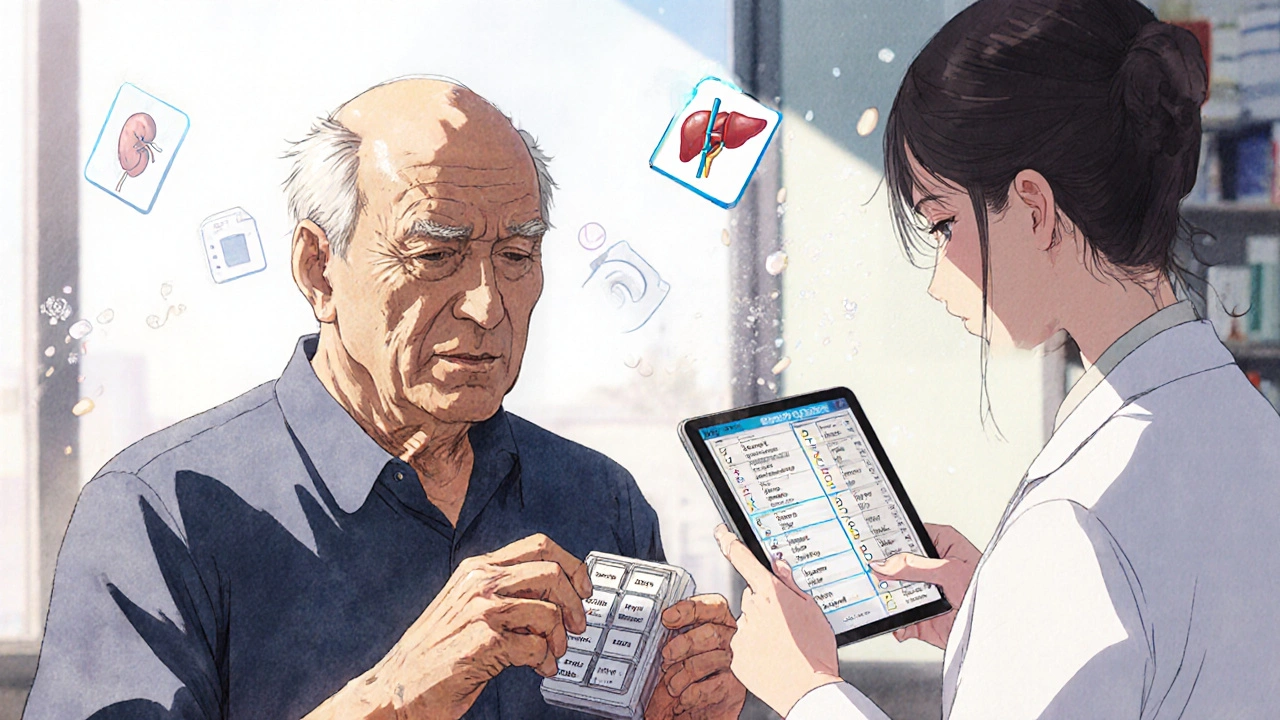

More than half of adults over 65 take five or more prescription drugs. That’s not unusual-it’s the norm. But each additional pill multiplies the risk of bad interactions. A blood thinner, a heart med, a painkiller, a sleep aid, and a stomach protector? Each one can interfere with the others. One drug might slow down how another is broken down. Another might make the kidneys work harder than they can. A 2016 study found that 55% of seniors take five or more medications. By 2022, medication errors were linked to 35% of hospital admissions in this group. The fix isn’t just cutting pills-it’s reviewing them. A “brown bag review,” where patients bring all their meds to the doctor, reduces errors by up to 40%. Pharmacists who specialize in geriatrics can spot hidden dangers in a 10-minute review.

What’s Missing from the Research

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most drug trials don’t include people over 75. In 2019, the FDA analyzed 218 major trials and found that 40% didn’t include a single participant over 75. That means doctors are often guessing how a drug works in someone who’s 80 or 90. The result? A huge gap in evidence. We know how metformin works in a 65-year-old with decent kidneys. But what about an 82-year-old with mild dementia, heart failure, and a creatinine clearance of 40? There’s no clear answer. That’s why real-world data-like the ASPREE trial-is so important. It showed that 40% of seniors needed dose changes within six months, even if they started with the “correct” dose.How to Get It Right

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Here’s what works:- Keep a full list of everything you take-including vitamins, supplements, and over-the-counter meds. Write down why you take each one.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist: “Is this dose right for my age and kidney function?”

- Request a kidney test (eGFR or creatinine clearance) at least once a year. Don’t wait until you feel sick.

- Use a pill organizer with alarms. Studies show it improves adherence by 37% when caregivers are involved.

- Ask about deprescribing. If you’re on five meds, ask if any can be stopped or lowered. It’s not failure-it’s smarter care.

What’s Coming Next

The future of geriatric dosing isn’t just about age. It’s about function. Researchers are starting to use tests like the Timed Up and Go (TUG)-where you stand up, walk 3 meters, turn, and sit down-to predict how well your body handles meds. If it takes more than 12 seconds, your risk of side effects goes up. That’s more useful than your birth year. The FDA is now requiring real-world data for 85 high-risk drugs. AI tools like MedAware are being tested to suggest safer doses based on your full health profile. By 2030, personalized dosing using kidney, liver, and cognitive data could become standard for most high-risk medications. But until then, the best tool you have is awareness. Your body isn’t broken. It’s just different. And medicine should be too.Why can’t seniors take the same dose as younger adults?

Aging changes how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and removes drugs. Kidney and liver function decline, body fat increases, and muscle mass decreases. These changes mean drugs stay in the system longer and can build up to toxic levels. A standard adult dose may be too strong and dangerous for someone over 65.

What is the Beers Criteria® and why does it matter?

The Beers Criteria® is a list of medications that are potentially inappropriate for older adults because they carry high risks of side effects like falls, confusion, or kidney damage. Updated every two years by the American Geriatrics Society, it helps doctors avoid drugs that are more harmful than helpful in seniors. It’s used in hospitals, nursing homes, and clinics to guide safer prescribing.

How do I know if my kidney function is low enough to need a dose change?

Your doctor can order a simple blood test to check your creatinine level and calculate your estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). If your eGFR is below 60 mL/min/1.73m², your kidneys are not filtering normally. If it drops below 50, most drugs cleared by the kidneys need a reduced dose. Ask for this test at least once a year if you’re over 65.

Are over-the-counter drugs safe for seniors?

Not always. Many OTC meds-like sleep aids with diphenhydramine, stomach meds with anticholinergics, or pain relievers like ibuprofen-can be dangerous for older adults. They’re not regulated for age-specific risks. Always check with a pharmacist before taking any OTC drug, even if it’s labeled “safe for all ages.”

Can I stop taking a medication if I feel fine?

Never stop a prescription without talking to your doctor. But you should ask if you still need it. Many seniors take medications they no longer need because no one ever reviewed them. A medication review can identify drugs that are no longer helping-or that are causing harm. Deprescribing is a normal part of good care, not a sign of failure.

How can a pharmacist help with medication safety?

Pharmacists trained in geriatrics can review all your medications, spot dangerous interactions, suggest safer alternatives, and help adjust doses based on your kidney or liver function. Studies show they reduce medication errors by 67% in older adults. Many pharmacies offer free medication reviews-ask for one.

Dana Dolan

November 19, 2025 AT 04:31My mum’s on five meds and her pharmacist caught three that were doing more harm than good. She’s 78, walks with a cane, and now she’s actually sleeping through the night. Just goes to show-sometimes less is more, even if it feels counterintuitive.

Also, why do we still let pharmacies sell Benadryl like it’s candy? It’s basically a dementia starter pack for seniors.

seamus moginie

November 20, 2025 AT 17:53This is the most important post I’ve read in years. I’m a retired GP and I’ve seen too many elderly patients hospitalized because some young resident prescribed them a standard dose of gabapentin. It’s not negligence-it’s ignorance. The system is broken, and it’s killing people slowly.

Ellen Calnan

November 22, 2025 AT 09:30There’s something deeply poetic about this: our bodies change, and yet our medicine doesn’t. We treat aging like a glitch to be fixed, not a natural evolution. The same pills that kept us running marathons at 30 become landmines at 75.

I keep thinking about how we celebrate youth but fear decay-and yet, the body’s wisdom is in its slowing down. Maybe the drug companies should start listening to the body instead of the profit margin.

Richard Risemberg

November 23, 2025 AT 06:48Man, I love how this post doesn’t just list facts-it paints a whole damn picture. You’ve got your kidneys slowing like a rusty faucet, your liver taking naps, your fat cells hoarding diazepam like little drug mules. And doctors? Still prescribing like we’re all 25 and bulletproof.

My aunt took a standard dose of a blood pressure med and ended up in the ER after fainting in the grocery store. She’s fine now, but it took a pharmacist with 30 years of geriatric experience to spot the problem. Why isn’t that mandatory?

Andrew Montandon

November 23, 2025 AT 18:28Okay, I’m not a doctor, but I’ve read this entire thing twice. And I’m telling you-this needs to be in every high school health class. Not just for seniors, but for their families. My mom’s on four meds, and I had no idea any of them could cause falls or dementia. I’m printing this out and taking it to her next appointment.

Also, the Beers Criteria? I’m saving that link. I’m gonna send it to every relative over 65 I know. This is life-saving info, not just ‘medical jargon.’

Sam Reicks

November 24, 2025 AT 01:40Who funded this? Big Pharma? They want us to think aging is a disease so they can sell us more pills. The real problem? Doctors are lazy. They don’t want to think. They just copy-paste the same script for every patient. Kidney function? Who checks that? The system is rigged.

Also, ‘dementia risk’? That’s just fearmongering. My grandpa took Benadryl for 20 years and he’s still playing chess at 92. Coincidence? Maybe. Or maybe you’re exaggerating to get clicks.

Reema Al-Zaheri

November 26, 2025 AT 00:24The Beers Criteria® is an essential clinical tool, and its updates are based on rigorous, peer-reviewed meta-analyses of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data in elderly populations. It is not a suggestion; it is a standard of care. The fact that it is underutilized reflects systemic failures in geriatric education and healthcare policy, not a lack of evidence.

Additionally, the Cockcroft-Gault equation, while widely used, has known limitations in obese and cachectic patients; the CKD-EPI equation is more accurate for eGFR estimation in modern practice.

Michael Salmon

November 26, 2025 AT 23:31Let’s be real: this is just another guilt-trip for doctors so they feel bad about prescribing. Seniors are taking too many pills? Then stop being so damn sick. If your kidneys are failing, maybe you shouldn’t have eaten all that salt and sugar for 50 years. You don’t get to live to 80 and then demand special treatment because you didn’t take care of yourself.

Also, ‘deprescribing’? That’s just code for ‘we’re too lazy to figure out what’s actually wrong with you.’

Joe Durham

November 27, 2025 AT 09:27I’m a son to a 79-year-old mom who’s on six meds. I used to think she was just being dramatic when she said she felt ‘off.’ Now I get it. I didn’t know kidney function dropped that fast. I didn’t know Benadryl could mess with her brain.

My mom’s doctor never mentioned any of this. I had to find it myself. I’m not mad-I’m just grateful this post exists. Maybe if more people knew, fewer families would be scrambling in the ER.

Derron Vanderpoel

November 29, 2025 AT 07:06I cried reading this. My dad had a fall last year after taking a sleep med. They said it was ‘just an accident.’ But I looked up the drug-diphenhydramine. It’s on the Beers list. He didn’t need it. No one asked if he needed it. They just wrote the script.

He’s okay now, but I swear, if I hadn’t found this post, I’d still be blaming him for being clumsy. This isn’t just medicine-it’s love. And we’re failing our parents by not knowing.

Timothy Reed

November 29, 2025 AT 20:48This is exactly the kind of practical, evidence-based guidance that’s missing from mainstream healthcare conversations. The ‘start low, go slow’ principle isn’t just good advice-it’s the ethical baseline for prescribing to older adults.

One suggestion: add a note about the role of care homes and nursing facilities in medication reviews. Many residents are on 10+ drugs, and the turnover of staff makes continuity nearly impossible. Standardized pharmacist-led audits could be a game-changer.

Christopher K

November 30, 2025 AT 19:08So now we’re supposed to believe that old people are too fragile for medicine? What’s next? No one over 65 gets antibiotics? This is socialism disguised as healthcare. You want to ‘deprescribe’? Fine. But don’t blame the doctors-blame the fact that people won’t just die quietly anymore.

Also, ‘AI tools’? Yeah, right. That’s just the next scam to get us to pay for more apps.

harenee hanapi

December 2, 2025 AT 11:16Everyone’s talking about this like it’s some big secret. But I’ve been saying this for YEARS. My neighbor’s husband died from a bleeding ulcer because he was on ibuprofen for his arthritis. No one warned him. No one asked. And now everyone’s shocked? This is why I don’t trust the medical system. They’re all just waiting for you to get old so they can profit off your decline.

And don’t even get me started on ‘pharmacists’-they’re just glorified cashiers who read off a screen.

Christopher Robinson

December 4, 2025 AT 08:11👏 This is the kind of post that makes me proud to be part of this community. Thank you for writing this. I’ve shared it with my entire family group chat. My grandma’s 84, and she’s on five meds. I’m taking her to the pharmacist next week for a brown bag review. 🙏

Also, the Timed Up and Go test? That’s genius. If you can’t stand up and walk in under 12 seconds, maybe your body’s telling you something. We need to stop measuring health by age and start measuring it by function. 🧠🫀