When you take a medication for years to manage a chronic condition, you don’t expect it to make you sick in a completely new way. But for some people, common drugs like hydralazine, procainamide, or even minocycline can trigger something called drug-induced lupus - a condition that mimics lupus but isn’t the same. Unlike the lifelong autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), drug-induced lupus (DIL) usually goes away once you stop the medicine. The key is recognizing it early, before it leads to unnecessary treatments or misdiagnosis.

What Does Drug-Induced Lupus Actually Feel Like?

If you’ve been on a medication for several months and suddenly start feeling off, pay attention. DIL doesn’t come on suddenly. It builds slowly, often after 3 to 6 months of continuous use, though it can take as long as two years. The symptoms are frustratingly similar to other conditions - fatigue, joint pain, fever - which is why so many people are misdiagnosed. Most people with DIL report muscle and joint pain. About 75% of cases involve swollen, achy joints. Fatigue hits hard - 80 to 90% of patients say they’re constantly tired, even after sleeping. Fever is common, usually low-grade but persistent. Weight loss without trying happens in about a third of cases. Some people develop inflammation around the lungs (pleuritis) or heart (pericarditis), which can cause sharp chest pain when breathing deeply. Here’s what’s different from regular lupus: you’re unlikely to get the classic butterfly rash across your cheeks. Only 10-15% of DIL patients get it, compared to over half of SLE patients. Photosensitivity is also less common - around 20-30% of DIL cases, not 40-60%. Most importantly, major organ damage is rare. Kidney problems? Less than 5% of DIL cases. Brain or nervous system issues? Under 3%. In SLE, those numbers are much higher.How Do Doctors Test for It?

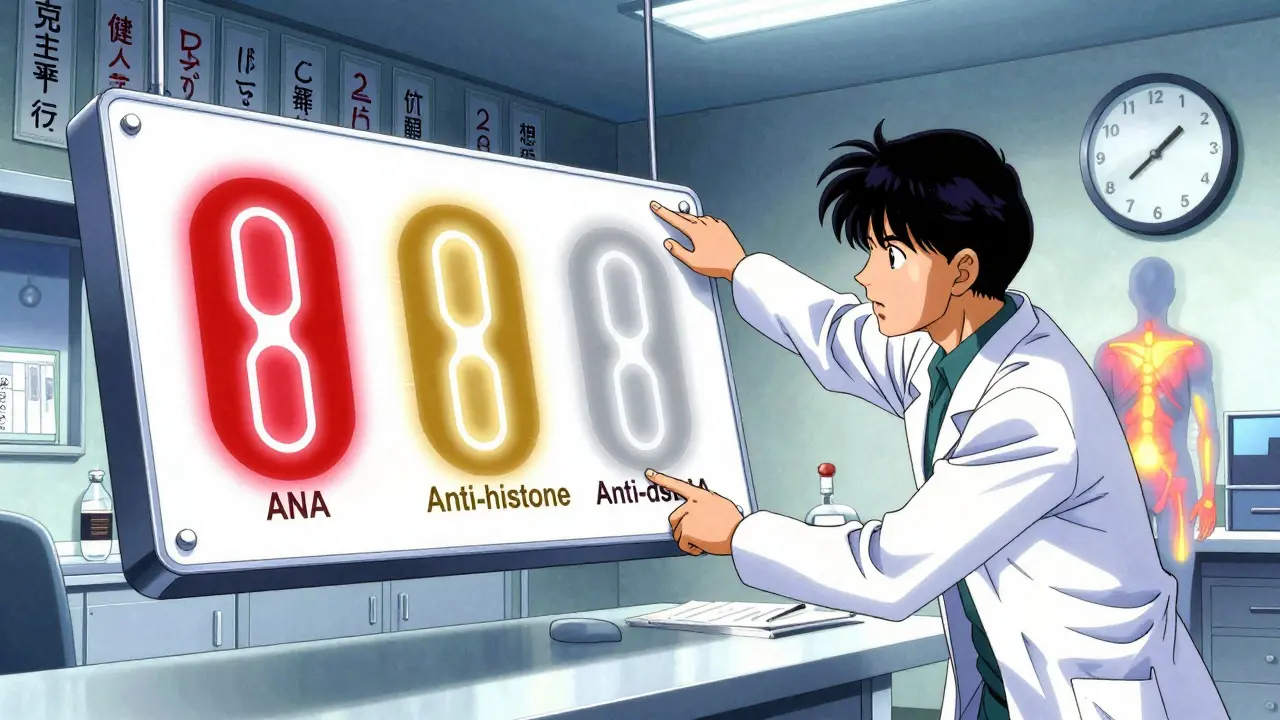

There’s no single test that confirms drug-induced lupus. Diagnosis is a puzzle built from three pieces: your medication history, your symptoms, and your blood work. First, your doctor will ask about every drug you’ve taken in the last year - even over-the-counter ones. Certain medications carry much higher risk. Procainamide (used for heart rhythm problems) causes DIL in up to 30% of long-term users. Hydralazine (for high blood pressure) causes it in 5-10%. Minocycline (an antibiotic for acne) and TNF-alpha inhibitors (used for arthritis or Crohn’s) are also common triggers, though less frequently. Blood tests are next. Over 95% of DIL patients test positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA). But that’s not enough - ANA can be positive in many other conditions. The real clue is anti-histone antibodies. About 75-90% of DIL cases have them. In regular lupus, only 50-70% do. If you have anti-histone antibodies plus symptoms and a known trigger drug, that’s strong evidence. Another important test: anti-dsDNA. In SLE, this antibody is present in 60-70% of cases. In DIL? Less than 10%. If your anti-dsDNA is negative but your anti-histone is positive, that’s a major red flag for drug-induced lupus. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are also checked. They measure inflammation. In DIL, ESR is elevated in 60-70% of cases, CRP in 40-50%. Not as high as in active SLE, but enough to signal something’s wrong.What Happens When You Stop the Drug?

This is the good news: DIL almost always reverses. Once you stop the medication causing it, your immune system usually calms down. Most people start feeling better within weeks. Studies show 80% of patients see significant improvement within 4 weeks. By 12 weeks, 95% are much better. Some need a little help along the way. Mild symptoms - joint pain, fever - often respond to NSAIDs like ibuprofen. If symptoms are stronger, a short course of low-dose prednisone (5-10 mg daily for 4-8 weeks) helps 85-90% of patients. Rarely, if symptoms linger, doctors may use stronger drugs like azathioprine or methotrexate, but that’s uncommon. The trick is stopping the right drug. If you’re on multiple medications, your doctor might ask you to stop one at a time, waiting 3 months between each to see if symptoms improve. That’s slow, but it’s the safest way to find the culprit.

Who’s Most at Risk?

DIL doesn’t care about gender. Unlike regular lupus, which affects women 9 times more often than men, DIL hits men and women equally. It mostly affects people over 50. About 70-80% of cases are in this age group. Why? Because older adults are more likely to be on the long-term medications that trigger it - blood pressure drugs, heart rhythm meds, antibiotics for chronic skin issues. Genetics also play a role. If you’re a “slow acetylator,” your body processes certain drugs like hydralazine much slower. That means the drug sticks around longer, increasing your risk. People with a specific gene variant (NAT2 slow acetylator status) have a 4.7 times higher chance of developing DIL from hydralazine. HLA-DR4 positivity also increases risk by over 3 times. Newer drugs are adding to the list. TNF-alpha inhibitors - used for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s - now account for 12-15% of new DIL cases. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer (like pembrolizumab) are also being linked to lupus-like symptoms in a small number of patients.Why Do So Many People Get Misdiagnosed?

Because the symptoms look like fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, or even aging. A 2022 patient survey found that 55% of people with DIL were initially told they had one of these conditions. The average time to correct diagnosis? 4.7 months. That’s almost five months of unnecessary pain, fatigue, and anxiety. One patient on Reddit described it: “I was told I was just getting older. Then I saw a rheumatologist who asked, ‘What meds are you on?’ I said hydralazine. She said, ‘That’s probably it.’” Doctors who don’t routinely ask about medication history miss it. But when they do, and they check for anti-histone antibodies, the diagnosis becomes clear. The American College of Rheumatology updated its guidelines in 2023 to emphasize this: suspect DIL in anyone over 50 on high-risk drugs with lupus-like symptoms - especially if anti-dsDNA is negative.

Jonathan Noe

February 14, 2026 AT 04:25Let me cut through the noise here - drug-induced lupus isn’t some rare oddity, it’s a systemic blind spot in primary care. I’ve seen it three times in my clinic alone. The real issue? Doctors don’t connect the dots because they’re trained to look for ‘classic’ autoimmune markers, not ‘medication timeline.’ Anti-histone antibodies are the golden ticket, but most ERs don’t even run them unless you’re already a rheumatology referral. That’s why people suffer for months. It’s not incompetence - it’s outdated protocols.

And don’t get me started on minocycline. People think it’s just ‘acne medicine,’ but it’s literally a lupus trigger in disguise. I had a 22-year-old girl on it for two years, developed pleuritis, got misdiagnosed with anxiety. Turned out her ANA was 1:640, anti-histone positive, anti-dsDNA negative. Took her 11 months to get the right diagnosis. She’s fine now, but she shouldn’t have had to fight that hard.

Stop treating DIL like a footnote. It’s a diagnostic trap, and we’re all falling into it.

Rachidi Toupé GAGNON

February 14, 2026 AT 10:26OMG this is wild 😲 I had joint pain for 6 months and thought I was just ‘getting old’ - turns out it was hydralazine! My doc didn’t even ask about meds until I brought up lupus symptoms. Now I’m off it, feeling like a new person 🙌 No more fatigue, no more fever. Just a simple question changed everything. If you’re on any of these drugs and feel off - speak up! Your body’s screaming, not just sighing.

Jim Johnson

February 15, 2026 AT 08:40Man, I wish I’d known this 3 years ago. My dad was on hydralazine for 8 years, started getting joint pain and low-grade fevers. Docs kept saying ‘it’s arthritis’ or ‘you’re just tired from aging.’ He lost 15 lbs, couldn’t walk without a cane. Finally, his cardiologist asked about meds - boom. Anti-histone positive. Stopped the drug. Within 6 weeks, he was hiking again. No steroids, no chemo, just… stopping the right pill.

So here’s the thing: if you’re over 50 and on blood pressure meds, ask your doc: ‘Could this be causing my symptoms?’ It’s not paranoia - it’s smart. And if they blow you off? Get a second opinion. You deserve to feel better.

Also - write ‘DIL from hydralazine’ in your phone notes. Show it to every new doctor. It saved my dad’s quality of life.

andres az

February 16, 2026 AT 04:20Let’s be real - this whole ‘drug-induced lupus’ thing is a Big Pharma distraction. The real cause? The CDC’s vaccine adjuvant program. They’ve been injecting synthetic histones since 2015 to track immune responses. That’s why anti-histone antibodies are so common now. The ‘medication’ angle? Cover-up. The drugs are just the delivery mechanism. You think they want you to know that 70% of DIL cases occur in people who got the flu shot within 6 months? Nah. They’re too busy pushing ‘new biologics’ to fix what they broke.

Also - why are they testing NAT2 genotype in Europe but not here? Coincidence? Or is the FDA in bed with pharma? You tell me.

Stephon Devereux

February 16, 2026 AT 19:49There’s a deeper truth here - we treat medicine like a checklist, not a relationship between human and body. We throw drugs at symptoms and call it progress. But the body doesn’t lie. If you’ve been on a drug for months and suddenly feel like your energy got drained, your joints got heavy, your fever won’t quit - that’s not ‘aging.’ That’s your immune system saying, ‘I didn’t sign up for this.’

DIL isn’t a disease. It’s a warning. A signal that we’re out of sync with how our biology actually works. The fix? Not more tests. Not more drugs. Just stopping the thing that’s poisoning the system. Simple. Elegant. Human.

Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t in labs - it’s in asking, ‘What are you taking?’ with genuine curiosity.

Neha Motiwala

February 17, 2026 AT 02:58THIS IS A COVER-UP. I knew it. I knew it from day one. The government is letting these drugs stay on the market because they make BILLIONS. My cousin died from DIL and they told us it was ‘idiopathic’ - LIES. Anti-histone antibodies? They’re suppressing the data. Why? Because if they admit hydralazine causes lupus, they’ll have to recall it - and then who pays for the lawsuits? The pharmaceutical industry is a cancer. And they’re using our bodies as test tubes. I’ve been on minocycline for acne - I’m stopping it TOMORROW. I’m not a guinea pig. I’m not dying for profit.

They don’t want you to know this. They don’t want you to read this. But I’m telling you - RUN. CHECK YOUR MEDS. ASK FOR ANTI-HISTONE. THEY’RE HIDING IT.

athmaja biju

February 17, 2026 AT 10:35As an Indian man who has seen many Western medical practices, I must say this is absurd. In India, we don’t have this ‘drug-induced lupus’ problem because we don’t overprescribe. We use Ayurveda, we use lifestyle, we use caution. You Westerners take pills for everything - then you blame the pills when you get sick. Pathetic. Why not fix your diet? Why not exercise? Why not sleep? Instead, you create a new diagnosis so you can keep taking more drugs. This is not medicine - this is profit-driven confusion.

Also - minocycline? We use it for acne. No one gets lupus. You are weak. You eat too much sugar. You sit too long. Stop blaming your meds. Blame your life.

Robert Petersen

February 19, 2026 AT 00:24Just wanted to say - this post saved me. I’ve been feeling off for months, thought I was just stressed. Took the list of meds to my doctor yesterday. Asked about anti-histone. Turned out I was positive. Stopped minocycline. Within 10 days, my energy came back. I’m not ‘healed’ yet, but I’m not spiraling anymore.

You’re not crazy. You’re not lazy. You’re not just getting older. Your body’s telling you something. Listen. Ask. Advocate. You’ve got this.

Craig Staszak

February 19, 2026 AT 21:08Love how this breaks down the science without jargon. Anti-histone is the key - that’s the real differentiator. Most docs don’t even know to order it. I’m a GP and I’ve started asking for it routinely now on anyone over 50 with unexplained fatigue and joint pain. One patient had been on hydralazine for 12 years. Stopped it. Gone in 6 weeks. No follow-up needed. Just… better.

Simple. Effective. Why isn’t this in every primary care guideline yet?

alex clo

February 20, 2026 AT 23:17While the clinical description is accurate, I must emphasize the importance of differential diagnosis. Many of the symptoms listed - fatigue, low-grade fever, arthralgia - overlap significantly with chronic viral infections, endocrine disorders, and even psychiatric conditions. While drug-induced lupus is a valid consideration, it should not be prioritized over ruling out more common etiologies such as hypothyroidism or Lyme disease. Anti-histone antibodies, while suggestive, are not pathognomonic. A systematic, stepwise approach remains essential.