Aspirin Ototoxic Risk Calculator

Quick Takeaways

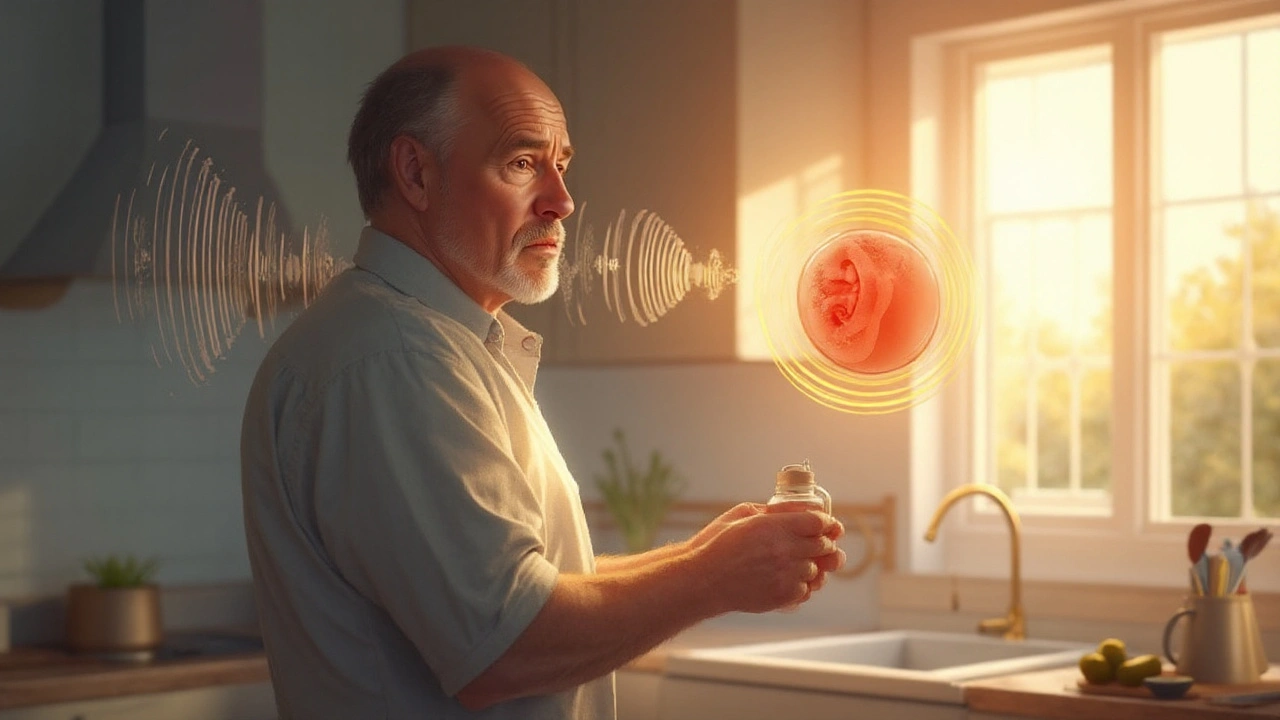

- Aspirin can cause temporary hearing loss and ringing in the ears at high doses.

- The effect is linked to salicylate buildup that interferes with cochlear hair cells.

- Most people recover once the drug is stopped, but repeated high‑dose use may cause lasting damage.

- Understanding the mechanism helps you balance pain relief against ear health.

Aspirin is a salicylate drug classified as a nonsteroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) that inhibits cyclooxygenase enzymes to reduce pain, fever, and platelet aggregation. While it’s a staple in households worldwide, research dating back to the 1960s flagged an unexpected side effect: hearing loss ranging from mild muffling to noticeable tinnitus (ringing). This article unpacks the biology, the dose‑response curve, and practical steps to protect your ears.

How Aspirin Interacts with the Auditory System

The inner ear relies on cochlear hair cells to translate sound vibrations into electrical signals. Salicylate molecules, the active form of aspirin, can cross the blood‑brain barrier and accumulate in the perilymph, the fluid bathing these hair cells. Elevated salicylate blood levels (usually above 30µg/mL) lead to two key disruptions:

- Mechanical stiffening: Salicylates bind to the outer hair cells’ motor protein prestin, reducing their ability to amplify sound. This manifests as a temporary drop of 10-20dB in high‑frequency hearing.

- Neurochemical interference: Aspirin’s inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) reduces prostaglandin production, which in turn alters the ion balance critical for hair‑cell function.

These effects are reversible for most people because the hair cells themselves remain intact; they simply regain their flex when the drug clears.

Dose‑Response Relationship: When Does the Risk Spike?

Most over‑the‑counter aspirin regimens (≤ 325mg per day) seldom cause noticeable auditory changes. The risk rises sharply when daily doses exceed 2-3g, a threshold often used in cardiovascular prevention or during acute inflammatory episodes. Below is a quick reference:

| Daily Dose | Typical Use | Ototoxic Risk | Mechanism Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 325mg | Pain/fever relief | Very low | Minimal salicylate buildup |

| 500mg - 1g | Moderate anti‑inflammatory | Low | Transient cochlear stiffness |

| 2g - 3g | Cardiovascular prophylaxis | Moderate | Salicylate‑induced hair‑cell inhibition |

| > 3g | Acute high‑dose therapy | High | Significant prostaglandin suppression & ion imbalance |

Note that individual susceptibility varies. Older adults, people with pre‑existing sensorineural hearing loss, or those on concurrent ototoxic medications (e.g., loop diuretics) may experience effects at lower doses.

Comparing Aspirin to Other NSAIDs

Not all NSAIDs share the same ear‑risk profile. Salicylate chemistry is unique to aspirin; ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib lack the same propensity to accumulate in inner‑ear fluids. Below is a snapshot comparison:

| Drug | Typical High Dose | Ototoxic Risk | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 3g/day | High | Salicylate accumulation, COX inhibition |

| Ibuprofen | 3.2g/day | Low | COX inhibition without salicylate buildup |

| Naproxen | 1.5g/day | Low‑moderate | COX inhibition, longer half‑life |

| Celecoxib | 400mg/day | Very low | Selective COX‑2 inhibition, no salicylate |

When a clinician needs anti‑platelet therapy but the patient has fragile hearing, they might opt for a low‑dose aspirin regimen or switch to an alternative antiplatelet that lacks ototoxicity.

Real‑World Cases: When Aspirin Changed the Soundscape

Consider Sarah, a 58‑year‑old marathon runner who began a 4‑gram daily aspirin regimen after a mild heart attack. Within two weeks she noticed a high‑pitched ringing after her morning runs. An audiologist measured a 15‑dB dip at 8kHz and confirmed salicylate‑related temporary threshold shift. After tapering the dose to 81mg and switching to low‑dose clopidogrel, her hearing returned to baseline in four weeks.

Contrast that with Mark, a 42‑year‑old construction worker who habitually took 2g of aspirin for chronic back pain while also using high‑dose acetaminophen. After six months he developed persistent tinnitus and a measurable loss at 6kHz. In his case, the combined ototoxic load likely pushed the hair cells past a reversible point, leading to a permanent deficit.

These anecdotes illustrate two key lessons: dose matters, and cumulative exposure to ototoxic agents can turn a reversible shift into lasting damage.

Managing the Risk: Practical Tips

- Know your dose. Keep daily aspirin under 1g unless your doctor explicitly advises higher.

- Monitor hearing. If you notice ringing or muffled sounds after starting or increasing aspirin, schedule an audiogram.

- Watch for drug interactions. Loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide), aminoglycoside antibiotics, and high‑dose NSAIDs can amplify ototoxicity.

- Consider alternatives. For pain, ibuprofen or naproxen are less likely to affect hearing; for antiplatelet therapy, low-dose clopidogrel or dipyridamole may be options.

- Stay hydrated. Adequate fluid intake helps clear salicylates from the inner ear more quickly.

For patients with pre‑existing sensorineural hearing loss, clinicians often prescribe the lowest effective aspirin dose and recommend routine audiological follow‑up.

What the Research Says

Large epidemiological studies from the 1990s onward, such as the British Medical Journal cohort of 113,000 adults, found a statistically significant association between high‑dose aspirin (>2g/day) and a 1.8‑fold increase in self‑reported tinnitus. More recent clinical trials using objective audiometry confirm a dose‑dependent temporary threshold shift that resolves within 48-72hours after discontinuation.

Animal models (guinea pig cochlear studies) have visualized salicylate‑induced reductions in outer‑hair‑cell motility, providing a mechanistic bridge between human symptoms and cellular changes.

Future Directions: Can We Prevent Aspirin‑Induced Ototoxicity?

Researchers are exploring antioxidant co‑therapies (e.g., N‑acetylcysteine) that may protect hair cells from oxidative stress caused by salicylates. Early phase‑II trials suggest a modest reduction in threshold shift magnitude, but larger studies are needed before clinical adoption.

Additionally, pharmacogenomic screening might identify individuals with slower salicylate metabolism, categorizing them as high‑risk for ototoxic side effects.

Bottom Line

The link between aspirin and hearing loss is real, dose‑dependent, and usually reversible. Understanding the underlying ototoxicity mechanisms equips you to balance cardiovascular or pain‑relief benefits against potential ear‑health costs. Keep doses low, stay alert to auditory changes, and discuss alternatives with your healthcare provider if you notice any symptoms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can occasional aspirin use cause permanent hearing loss?

Rarely. In most healthy adults, occasional use (≤ 325mg) leads only to a temporary slight shift that resolves within a day. Permanent loss usually requires chronic high‑dose exposure or a combination with other ototoxic drugs.

Is tinnitus always a sign of aspirin‑related damage?

No. Tinnitus can stem from many sources-stress, earwax, noise exposure, or other medications. However, if it appears shortly after starting a high dose of aspirin and fades when the drug is stopped, aspirin is likely the cause.

Should I stop my low‑dose aspirin if I have mild hearing loss?

Low‑dose aspirin (81mg) carries a very low ototoxic risk. Most clinicians recommend continuing it for cardiovascular protection, but discuss any concerns with your doctor, especially if you notice new symptoms.

Are there any foods or supplements that can counteract aspirin’s ear effects?

Staying well‑hydrated helps the body clear salicylates faster. Some studies suggest antioxidants like vitamin C or N‑acetylcysteine may reduce oxidative stress in the cochlea, but evidence is still preliminary.

What tests do audiologists use to detect aspirin‑related changes?

Pure‑tone audiometry across 250Hz-8kHz is standard. A sudden dip at high frequencies (6-8kHz) after high‑dose aspirin suggests a temporary threshold shift. Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) can also reveal outer‑hair‑cell stiffness.

Shanmughasundhar Sengeni

September 23, 2025 AT 02:03Look, the whole “aspirin is harmless” myth falls apart when you actually read the data. High‑dose salicylates shove themselves into inner‑ear fluids, mess with ion balance, and turn your cochlea into a squeaky‑toy. Most people think a little pill can’t touch your ears, but the science shows otherwise. If you push past 1 g a day, the risk jumps from negligible to noticeable, especially if you’re already dealing with age‑related hearing loss. It’s not some conspiracy, it’s just pharmacology doing its thing. So before you down that extra 500 mg for “heart health”, ask yourself if your ears can handle the extra load.

ankush kumar

September 23, 2025 AT 03:13Hey folks, let me break this down in a way that actually sticks – even if you’re juggling a full‑time job, a family, and that dreaded ‘to‑do’ list that never ends.

First off, the dose‑response curve for aspirin isn’t some linear ‘more is better’ story; it’s more like a steep hill that you only want to climb when you’re wearing the right gear.

When you hit 2‑3 g per day, you’re basically flooding your bloodstream with salicylates that love to hang out in the endolymph, the fluid bathing your hair cells.

That overload creates a temporary threshold shift, which feels like someone turned up the static on your favorite song.

Now, most healthy adults will shake it off in a couple of days, but the damage can become permanent if you combine aspirin with other ototoxic agents like loop diuretics or aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Think of your inner ear as a delicate orchestra – add too many salty notes and the violins start to go out of tune.

Even something as simple as dehydration can slow the clearance of salicylates, making the problem linger longer.

So, sip water like it’s your job; you’ll help your kidneys flush the excess faster.

If you’re already dealing with mild sensorineural loss, keep your aspirin below 81 mg unless your cardiologist says otherwise – the risk outweighs the benefit at higher doses.

And remember, not all NSAIDs are created equal; ibuprofen doesn’t stockpile in the cochlea the way aspirin does, making it a safer pick for occasional pain relief.

But don’t use ibuprofen as a free pass either – every drug has its own side‑effect profile.

What really helps is regular hearing checks – a quick audiogram can catch the subtle high‑frequency dip before you notice it in daily life.

Many audiologists now use otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) to spot outer‑hair‑cell stress even when pure‑tone thresholds look fine.

If you spot a dip, the first move is to taper the aspirin, not to panic and stop a life‑saving medication without consulting your doc.

In short, treat aspirin like a double‑edged sword: great for blood‑clot prevention, but wield it with caution when your ears are in the line of fire.

Stay informed, stay hydrated, and keep the volume at a reasonable level – your ears will thank you.

josh Furley

September 23, 2025 AT 04:36People love to paint aspirin as the ultimate villain for tinnitus, but what if the real culprit is our obsession with “quick fixes”? 🤔 The body’s natural response to inflammation is a sophisticated cascade, and slamming it with a megadose of salicylates is like trying to silence an orchestra with a sledgehammer. Sure, you’ll get a temporary threshold shift, but that’s just the system yelling “enough!” – a reminder that we’re over‑medicating our way through discomfort. If you strip away the jargon, the takeaway is simple: moderation beats extremism, every single time. 🚀

Jacob Smith

September 23, 2025 AT 06:00Stay hydrated, folks!

Chris Atchot

September 23, 2025 AT 07:23Indeed, the dosage thresholds are critical; you’ll find that keeping daily aspirin under 1 g dramatically reduces the odds of any measurable high‑frequency dip; moreover, combining it with proper audiometric monitoring creates a safety net that most patients overlook; it’s like adding a seatbelt to an already safe car – an extra layer of protection you can’t afford to ignore.

Shanmugapriya Viswanathan

September 23, 2025 AT 08:46Listen up, everyone – the real reason we hear about “aspirin ototoxicity” is because Western pharma pushes the narrative to sell more “special” drugs, while we in India have known for decades that low‑dose aspirin is harmless if you respect the ancient Ayurvedic balance 😊. If you take a cue from our traditional practices, you’ll never need to worry about tinnitus from a single 81 mg tablet, because we trust the body’s own healing rhythm, not a foreign chemical flood.

andrew parsons

September 23, 2025 AT 10:10It is ethically incumbent upon healthcare providers to disclose the ototoxic potential of high‑dose aspirin with unequivocal clarity; patients deserve full transparency regarding both the cardiovascular benefits and the auditory risks associated with salicylate therapy; failure to do so not only undermines informed consent but also contravenes the fundamental principle of non‑maleficence; therefore, clinicians should incorporate routine audiological assessments into any treatment plan involving dosages exceeding 1 g per day; only through such diligent stewardship can we safeguard both heart health and auditory integrity 😊.

chioma uche

September 23, 2025 AT 11:33Enough of this western‑centric fear‑mongering! Our own people have survived on low‑dose aspirin for generations without a whisper of ringing in the ears – the real problem is the imported “big pharma” agenda trying to scare us into buying their overpriced alternatives. Wake up, defend our health sovereignty, and stop buying into these fabricated risks!